Part Two : Modern Patriarchy

The Kanun is dead

Nietzsche said: “God is dead” (17) to describe the substantial loss of values driven by religion. Some Albanians might thus say, “The Kanun is dead,” because various factors, notably global socio-economic changes, have brought about predominant shifts in Albania, making it difficult today to clearly recognize Albanian values. Honor, the word given, and hospitality would be undermined. Thus, some nostalgic for these lost values regret a transition they perceive as abnormal, in which the place of women serves as a measure. They partially blame women for the ills of Albanian society, particularly due to the false image spread by television, the media, and Albanian artistic circles, which are out of sync with the everyday reality that Albanian women face in overcoming obstacles on their path to emancipation. For some, the patriarchal system vanished because women behave like debauched individuals: “Women have all the rights today, even too many,” they say. One might wonder why some women, particularly singers, accept to propagate a negative and degrading image of women. In reality, these behaviors are typical of patriarchal societies, which still affect European countries today. Through the lens of men, these behaviors result from a desire for equality with men. Music thus appears as the easiest way, through physical appearance, to gain financial independence and be seen as an equal to men. These women are belittled, while paradoxically, it is the patriarchal traditions, defining them solely as sex, that provided women with a way to break free from men’s control. Conversely, intellectual women, who have found other means of being regarded on equal footing with men through their studies, are continually reduced by men to mere objects of sex and consequently struggle to express their opinions in Albanian patriarchal society.

It must be acknowledged that there has indeed been some liberation and progress in the treatment of women among Albanians. However, traces of this unacknowledged patriarchal tradition persist beyond Albanophone borders (18). Albanian women in the diaspora also face similar issues. They have found themselves in a society where women have more freedoms and have had to navigate the differences between family life and the society of their host country, especially for second-generation women. Today, very few Albanian women marry non-Albanians, even among third-generation women. As a result, cultural affinities and origin, as much as they may bring individuals closer, prevail over what should be prioritized in a relationship: love. These women thus wear blinders, limiting themselves to loving only Albanians and suppressing the possibility of a relationship with non-Albanians. This action is also claimed in the name of a certain paranoid patriotism, asserting the need to preserve the nation and Albanian blood. One must imagine the difficulty for these women to escape the rules imposed by men; taking the risk of marrying a non-Albanian means being repudiated by all family members. It may be romantic and naive to think that marriages happen out of love, but if we admit that marriages today are based on economic conditions, the lack of reciprocity in these demands inevitably creates a significant disadvantage for women. The exception would be in cases where young women from the diaspora marry men from Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia, as the economic resources of the women in these cases are superior to those of the men. However, the men then move in with their wives in a new apartment, seek work, and decide to take control of the household’s finances, while, conversely, women who move into their husband’s family remain confined to the home. If the Kanun is dead, it is not entirely dead for women, who are still at an immeasurable threshold of their freedom. “The Kanun is dead, long live the Kanun!”

Albanian Modernity

“Modern,” this term has become the buzzword for Albanians in the last decade. A sitcom was even created in 2002 called “Familja moderne” (The Modern Family). This imaginary and caricatured family had nothing modern about it, in the Western sense that Albanians claim, but it did correspond to their own conception of what modernity means. So, what is modernity for Albanians? This conception is ambiguous. For some, it means providing all possible opportunities for their children’s personal development while respecting certain family values. For others, it means completely stepping back from their children’s education, letting them make their own choices, and parents not wishing to interfere with their children’s vision of happiness. More often than not, however, it involves mimicking Western European life. It’s about doing like others, to avoid the disapproving gaze of the new “moderns”; “We are not backwards,” I’ve sometimes heard Albanians say. However, there is a clear difference in treatment between girls and boys. The word “moral,” she has morals (është e moralshme), often appears among Albanians, and it is only associated with young girls of the age to study and occasionally escaping family surveillance. Showing morals means not sleeping with men and keeping one’s virginity for the future husband, whereas men are encouraged to have sexual experiences. These attitudes reveal a hypocritical behavior in Albanian society, because if young men must have sexual experiences with other young women, these women are inevitably the daughters of some of these men. Virginity, for the future husband and even more so for his parents, is an essential asset that will determine a woman’s selection. These behaviors have led to a deviation on the part of women to adapt to this collective thought of preserving virginity, although it also involves a number of sacrifices.

Kurvë

The relative freedom granted to women living in Albania and those in the diaspora has not prevented a girl who is dating a boy not from her family from being considered a kurvë (prostitute). A woman who has a child out of wedlock is a whore; a woman who lives freely her sexual life is also a whore; a woman from the diaspora is a whore; a woman who is studying is a whore because “you never really know what she’s doing with boys far from home,” I’ve heard some say; a woman who has a friendly relationship with a man is also a whore, and if she is seen laughing with this man, she is doubly a whore simply because this behavior is connoted as an act of pure debauchery. Thus, most Albanian women would be whores except for the “Qika e shpis” (daughter of the house). These women, typically present today in more traditional families, are considered healthy and moral, because since the end of their secondary school studies at the latest, they are confined to serving their mothers and are shut in at home making napkins (tentene); awaiting the fateful arrival of Prince Charming in his Mercedes who will offer her a dream life abroad. However, the dream will quickly consist of serving her husband’s family. With a benevolent mother-in-law, caring sisters-in-law, and protective brothers-in-law, it seems evident that she will have impeccable morals, because at no point in her life will she have been free. This was also the condition for most women from rural Albanian families more than 20 years ago. These “daughters of the house” still exist, although their numbers have greatly decreased due to the various factors we have seen earlier. These daughters of the house have turned into semi-free girls who now live in what are called modern families. They are allowed to study because there is a certain intellectual competition. To please men, a certain level of education is required, more precisely, it is about finishing secondary school by the age of 18–19. Then, if they are still not married, they will always have the option to pursue higher education to extend their freedom and, incidentally, find a man before it is their father who chooses him. Free women, meaning the minority who live fully their sexual freedom, are still considered by others as whores. The lack of solidarity among women from the different categories described above results in each treating the other as a whore. Thus, for the daughters of the house, all women different from them are whores, and for the semi-free girls, it is the free women who are.

Virginity

For Albanians, a “kurvë” (whore) is a woman who has lost her virginity before marriage. Although nowadays, sexual relations after engagement are tacitly allowed, as long as the couple has the chance to see each other before the marriage, virginity remains a significant concern for Albanians. The young girl raised in her family must remain a virgin for her future husband. However, the so-called modern Albanians consider the virginity of their son’s future wife more important than the virginity of their own daughter. To marry off their son, families are more likely to seek young girls from traditional homes, even turning to the prostitution market. This is why men from the diaspora are more inclined to marry girls from Albania, Kosovo, or Macedonia. These young girls offer a greater guarantee of virginity and are also considered to be more docile. On the other hand, girls from the diaspora are seen as “kurvë,” simply because they go to clubs, have fun, drink, and talk to boys. However, Albanian girls, regardless of their origin, are not all virgins. How do they marry and gain acceptance from men? This myth of virginity and respect for traditions has led these young women to adopt different behaviors. To understand this, let’s define exactly what virginity means. In French, the word “vierge” (virgin) is ambiguous — it refers to a woman who has never had sexual relations, more specifically, a woman who has not lost her hymen. A man, by definition, can never be a virgin. However, the term “virginity” refers to both sexes as individuals who have never had sexual relations. Because of the ambiguity of the terms related to a woman’s virginity, I have created my own definitions. I have defined four types of virgins: 1. The virgin. 2. The non-virgin. 3. The half-virgin. 4. The pseudo-virgin. An explanation of the virgin and non-virgin categories seems unnecessary given their explicit nature. A half-virgin is a woman who practices oral or anal sex, but keeps her vagina reserved solely for her future husband, whom she doesn’t yet know. A pseudo-virgin is often a half-virgin, but more commonly, she is a non-virgin who has had her hymen reconstructed, commonly referred to as “getting stitched up.” Some pseudo-virgins manage, through certain tricks linked to their menstrual cycle, to convince their fiancé that they are virgins. My apologies, ladies, for exposing these age-old tricks. Albanian girls still do not live freely regarding their sexual lives. Half-virgins submit to men by providing them pleasure without receiving any in return. In this way, they succumb to societal pressure exerted by men, who seek sexual liberation while preserving the sacred core of their femininity as defined by these same men. Pseudo-virgins are in the same cycle. The loss of their virginity is often due to youthful mistakes or previously assumed sexual relations, which, after experiencing romantic disappointments, they turn towards traditional family structures. Albanians believe that sexuality is something degrading for young women, that it is only the domain of prostitutes and married women. If, for Albanians, being an unmarried woman and having sexual relations makes one a “whore,” why would an Albanian mother not be considered one, since she has relations with her husband? My mother’s name is not Mary, but I am irrefutable proof of intercourse. I have other proofs as well — having a brother and a sister, I am certain my parents had at least three sexual encounters in their lives. Aside from boasting about their exploits, sexuality remains a taboo subject for men. There is a kind of denial of sexuality in Albanian society. This discomfort is expressed, for example, when discussing sexual violence against women during the Kosovo war. This subject cannot be brought up without feelings of shame and dishonor, as if these women in this so-called modern society have something to be ashamed of and must live reclusively, hidden by shame. Once again, it is the will of men to refuse to acknowledge that mothers can also be sexual beings, and that this sometimes involves overcoming trials.

Divorce

“§33 Article 13. The woman has the duty: to preserve her husband’s honor, to serve him without reserve, to remain under his authority, to fulfill the marital duty, to raise and educate the children in honor, to maintain clothing and shoes, and not to interfere in the engagements of her sons and daughters.”

The rise in divorce cases among Albanians is seen as a terrible failure. In most cases, the fault is placed on the woman. She is a bad wife who failed to satisfy her husband’s needs and failed in her duties as outlined in the excerpt from the Kanun above. The man, on the other hand, is blameless; how could he not be, if he works and supports his family? His role is an indisputable success. The services the woman renders to the man, including sexual relations, form his only connections with her; the mistake can only be on her part. Moreover, the woman never gets custody of the children, as they belong to the father’s family. A divorced woman loses all ties with her ex-husband’s family and will never be able to see her children again. The divorced woman has sullied the reputation of her family and dishonored herself, as she did not fulfill what her status as a woman dictated. Here are some actions allowed by the Kanun for men:

“§57 Article 28. If a man beats his wife, he is not at fault according to the Kanun, and even her parents cannot take him to court.”

“§58 Article 33. The husband has the right to beat and chain his wife when she despises his orders.”

Most women do everything they can to keep their husband. Their lack of independence and support allows the most ill-intentioned husbands to take advantage of them, deceive them, and even beat them, without them being able to do anything but accept their fate. Divorce, for them, is synonymous with something much worse. It means dishonor, shame, and, above all, an inability to survive in an unfamiliar environment. They are sometimes deliberately kept in this state of dependence by the husband who wants to preserve his masculine essentiality. Divorce today reflects this realization by women who no longer wish to endure their husband’s wrath and who have the financial means to free themselves. Simone de Beauvoir compares the relationship of married couples to that of a master and slave, and here’s what she says:

“The master and the slave are also united by a mutual economic need that does not free the slave. In the master-slave relationship, the master does not express the need he has for the other; he holds the power to satisfy that need and does not mediate it; on the other hand, the slave, in dependence, hopes or fears, internalizes the need he has for the master; the urgency of the need, even if equal in both, always works in favor of the oppressor over the oppressed.”

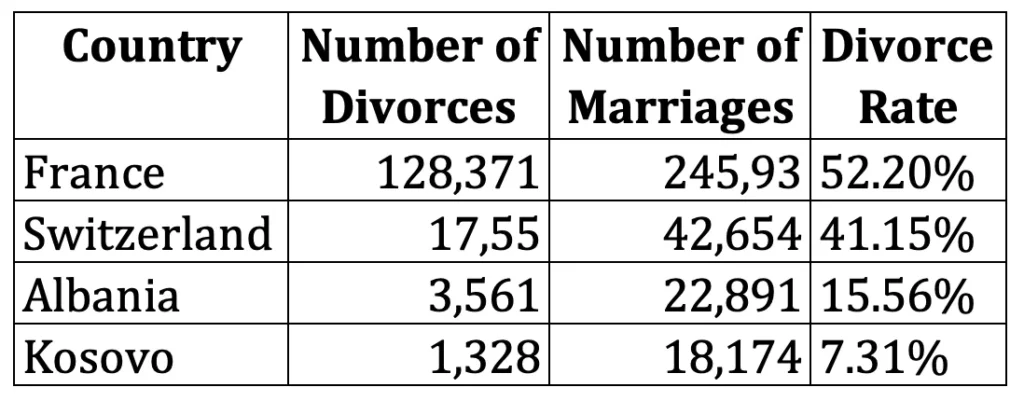

Divorce rate for the year 2012 (22):

What if the Albanian Mother Were a Prostitute ?

Everywhere in the world, prostitutes have always been seen as the dregs of society, those who occupy the lowest rung of the social ladder; the same is true among Albanians. It is often the precariousness of their existence that pushes these women to take up this profession. Thus, it is difficult to determine whether this constitutes a true choice. However, we can ask ourselves when the Albanian woman has the opportunity to make a choice. From a very young age, she is conditioned to serve men; by adolescence, she is already seen as a future wife; upon marriage, she is reduced to a womb before becoming a mother, a slave to her husband and children.

“The married woman is a slave who must be placed on a throne.” — Balzac

The mother is universally a sacred, untouchable being. Any idea of degrading her is sacrilege. She is a being sacrificed on the altar of maternity; she is devoted to her husband and children; she is a virgin, an asexual myth for them, and it is precisely because she is considered as such that she is reduced to being only sexual, to being the Other. Balzac’s quote sums up what a mother is for Albanians. While she possesses the characteristics of a slave and a prostitute, she is a queen on a throne for her own children. It is this hypocrisy of Albanian society towards the mother that elevates her to a higher status than that of the prostitute. Meanwhile, defenders of patriarchy, heirs of the Albanian tribal-feudal system, subjugate their wives while belittling women who seek independence and equality with men. These same men are responsible for young girls continuing to be compared to prostitutes, relegated solely to what defines them as a sex. They are led to adopt behavior towards men because they cannot define and claim their own sexuality. Albanians only see the visible part of the iceberg that is sexual freedom, without perceiving the submerged part containing feminist demands, their desire for equality, and their wish to no longer be seen as the Other. Any attempt at freedom on the part of women does not exclusively mean the quest for sexual freedom, but this is what these attempts are reduced to by Albanians. Typically, they see prostitutes only through the lens of sexuality. For them, everything related to sexuality is related to prostitution, and everything related to freedom is inherent in sexuality. This is why a free girl is for them absolutely a prostitute. However, we have seen that the status of the mother assumes that she has a sexual life. Thus, the essential difference between an Albanian mother and a prostitute lies not in their sexuality but in their financial independence from men. We have seen that the Albanian mother has no economic independence; if she works, it is because the husband agrees; the money she earns is managed by him, while prostitutes manage their own money. Mothers are the hidden prostitutes of Albanian society, but they are accepted by it because they only have one unfaithful client. For Albanians, girls from homes would then be future prostitutes; housewives and mothers would be prostitutes in practice; and if a Jack the Ripper were to exist in Albania, his victims would be housewives and not prostitutes. Gentlemen, why not rejoice? We can finally shout unabashedly: “All prostitutes! Our mothers and our sisters too!”

To end this article on a cheerful note, we suggest listening to this song by GiedRé: “TouTes des puTes.”

Footnotes:

17. Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Paris: GF-Flammarion, 2006, p. 47.

18. Here is a personal anecdote: an Albanian who believes himself to be a modern person and thus emancipated from Albanian patriarchal values came to spend an evening with other Albanian friends at my place. When leaving, to give a kiss to my sister, who was in front of him, he asked for my permission. I replied that my sister was an adult, that I didn’t dictate her actions, and that he could ask her; if she disagreed, she would tell him. My sister, stunned, agreed to give him the kiss. She later admitted that she felt insulted because, according to him, she didn’t exist as an individual, that she depended on me, her brother, who controlled her actions. This blatant expression of male dominance clearly shows the environment in which Albanians in the diaspora still operate today.

19. The definitions of the words “virgin” and “virginity” are taken from the Petit Robert, 2014 edition.

20. The technical term is: hymenoplasty.

21. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex: Volume I, Paris: Gallimard Editions, folio essays, 1949 reissue of 1976, p. 22–23.

22. The latest statistics on this data for Kosovo date back to 2012. To offer a more relevant comparison with other countries, I decided to base myself on that year.

23. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex: Volume I, Paris: Gallimard Editions, folio essays, 1949 reissue of 1976, p. 193.

Sources:

Books:

DOJA Albert, Naître et grandir chez les Albanais : la construction culturelle de la personne, Paris: Éditions l’Harmattan, 2000, 322 p.

GJEÇOVI Shtjefën, Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit: The Code of Lekë Dukagjini, Albanian text with parallel English translation by Leonard Fox, 1874–1929 (Gjeçovi), 1989 (Fox), New York: Gjonleka Publishing Company. 269 p.

GJEÇOVI Shtjefën, Le Kanun de Lekë Dukagjini: Traduit de l’albanais par Christian Gut sur l’édition de Shtjefën Gjeçovi, Pejë: Dukagjini publishing House, 2001, 298 p.

DE BEAUVOIR Simone, The Second Sex: Volume I: Facts and Myths, Paris: Gallimard Editions, folio essays, 1949 reissue of 1976, 409 p.

DE BEAUVOIR Simone, The Second Sex: Volume II: The Lived Experience, Paris: Gallimard Editions, folio essays, 1949 reissue of 1976, 652 p.

NIETZSCHE Friedrich, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by Geneviève Bianquis, Paris: Flammarion 1996, 2006 for this edition, Paris: Aubier for the translation, 1969, 477 p.

CORBIN Alain, Le mal nécessaire?, l’Histoire: Prostitution: de la tolérance à la prohibition, January 2013, №383, p. 38–41.

RIPA Yannick, Comment on a aboli les maisons closes, l’Histoire: Prostitution: de la tolérance à la prohibition, January 2013, №383, p. 42–51.

FRONDIZI Alexandre, Les trottoirs de la Goutte-d’or, l’Histoire: Prostitution: de la tolérance à la prohibition, January 2013, №383, p. 52–55.

REVENIN Régis, Du côté des garçons, l’Histoire: Prostitution: de la tolérance à la prohibition, January 2013, №383, p. 56–57.

TARAUD Christelle, Visite au Sphynx d’Alger, l’Histoire: Prostitution: de la tolérance à la prohibition, January 2013, №383, p. 58–61.

DUPONT-MONOD Clara, Faut-il interdire la prostitution?, l’Histoire: Prostitution: de la tolérance à la prohibition, January 2013, №383, p. 62–65.

KADARÉ Ismaïl, Le Général de l’armée morte, Paris: Albin Michel, 1970, 287 p.

KADARÉ Ismaïl, Avril brisé, Paris: Fayard, 1981, 216 p.

KADARÉ Ismaïl, Eschyle ou le Grand Perdant, revised and expanded edition, Paris: Fayard, 1988, 1995 for the expanded edition. 185 p.

KADARÉ Ismaïl, La Fille d’Agamemnon, Paris: Fayard, 2003, 123 p.

Websites:

http://www.wellnesskliniek.com/fr/chirurgie-genitale/reconstruction-hymen

http://www.chirurgien-esthetiqueparis.com/Hymenoplastie

(Statistics: Marriages and Divorces)

http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/fr/index/themen/01/06/blank/key/06/06.html

http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/fr/index/themen/01/06/blank/key/05.html

http://www.insee.fr/fr/methodes/default.asp?page=definitions/taux-divorce.htm

https://ask.rks-gov.net/ENG/latest-news/328–press-release-marriages-and-divorces

http://www.instat.gov.al/al/themes/popullsia.aspx