I dedicate this article to the future prostitute in my life.

“Everything men have written about women should be suspected, for they are both judge and party.” — François Poullain de la Barre.

NB: For a more comfortable reading experience, this article is divided into two parts. However, its structure is designed as a single piece. The first part, Conditioning, and the second part, Modern Patriarchy, are inseparable, which is why they are published on the same day.

First Part : Conditioning

Foreword

One day, I caught my parents arguing. They had returned from vacation in Albania a few days earlier, and my father was reproaching my mother for talking and joking too much with a stranger. My father saw me enter and continued his speech in front of my mother. Then, he turned to me and asked :“And on top of that, I was there! What would she have done if I hadn’t been?” I immediately replied :“E qeshtu kur ta marrish një kurvë për grue.” (That’s what happens when you take a whore for a wife.) My father fell silent, eyes wide open, while my mother burst into laughter. However, I was overcome by a feeling of discomfort, almost shame — I had indirectly called my own mother a whore. That thought quickly faded, though, because in reality, I had only put into words what my father was already implying.

The Other

The word whore in Albanian translates to kurvë (1). This term is often used to describe a woman of loose morals. However, among some Albanians, it carries a much more ambiguous meaning than elsewhere. Indeed, a young girl who dares to associate with a boy is often labeled as a kurvë. Independence — both economic and personal — is, according to them, an inherent trait of a prostitute. In reality, during this transitional period that Albanians are experiencing, most young women are called whores. So why would the mother be an exception ? A prostitute is someone who consents to sexual relations in exchange for payment. Since the Albanian mother does not engage in such a profession, she cannot be considered one — or so I’ve been told. Yet, these young women whom Albanians label as kurvë do not practice this profession either. Who are these Albanians ? The political, social, and economic situation of Albanians is no longer what it was 20 years ago. That’s why it is difficult to define precisely who these Albanians are and extract from them an inherent characteristic — whether they are from Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, or the diaspora; whether they are considered modern or traditional; whether they come from different regions, religions, rural or urban backgrounds. However, despite this chaotic diversity, one constant emerges: the status of women still struggles to break free from primitive Albanian beliefs.

For Simone de Beauvoir, women are seen by men primarily as sexual beings. While a man defines himself simply as Man, a woman is determined and differentiated in relation to him — never the other way around. Man is the essential being, the Subject; woman is the Other (2). Thus, if young Albanian women are labeled as kurvë — reduced solely to their sexual identity — then we can assume that the same applies to Albanian mothers. Through their subjugation, they take on the role of what Simone de Beauvoir defines as the Other. Moreover, in her essay The Second Sex, the French philosopher quotes Antonio Marro, who states:“Between those who sell themselves through prostitution and those who sell themselves through marriage, the only difference is in price and the duration of the contract.” (3) Indeed, my mother was sold by her family to my father’s family. This was not necessarily a bad thing, and I wish to thank my grandparents for this arrangement. Because even if it was a mistake at first, it was corrected by the birth of my brilliant and masculine self — which, of course, justifies all forced and arranged marriages on earth. My mother did not resist because, like most Albanian women, she was conditioned from childhood for that fateful day: her wedding. So, what if the Albanian mother were a prostitute? To answer this question, we will examine the different stages of an Albanian woman’s life — like my mother’s — from birth to youth, then from her role as a wife to her ultimate ascension to the status of mother in Albanian patriarchal society.

Family Homogeneity

To understand the place of women in Albanian society, one must observe them within the primary vehicle of socialization: the family. The Albanian family system is homogeneous, meaning it consists of multiple couples living under the same roof. The patriarch or head of the household (zoti i shtëpisë) is the representative of family authority. His sons and grandchildren live in the same house with their wives. The separation of brothers often occurs upon the patriarch’s death. In rural areas, the Albanian household is frequently structured in this way. The women who marry into the household are considered outsiders: mall i huaj (someone else’s property). Only the patriarch’s daughters and granddaughters are regarded as integral parts of the family — until the day they, like their mothers before them, are married off into another group.

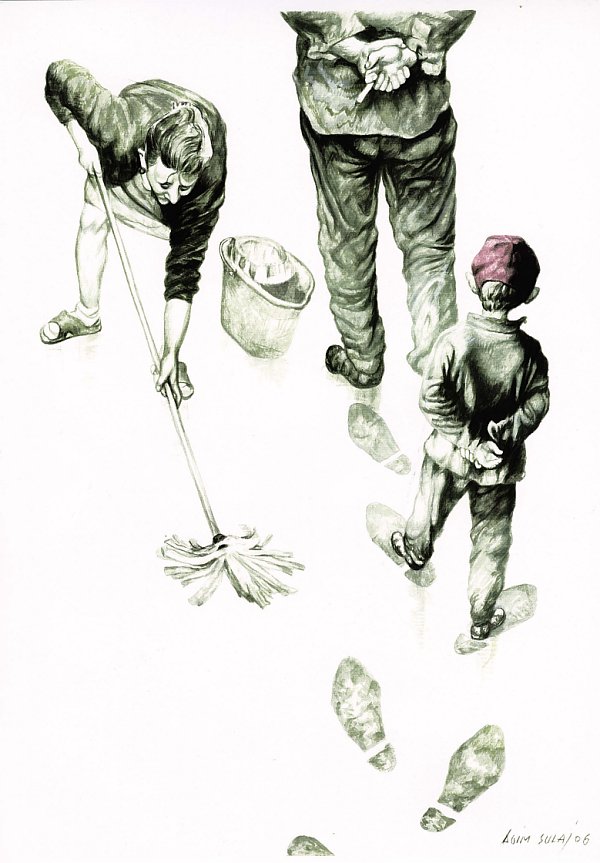

In Albanian families, children are treated as “miniature adults” (4). Depending on their gender, they are assigned daily tasks that condition them for their future roles within the family — roles they have already begun to identify with by observing their parents. The defining trait of a woman’s status is her ability to perform domestic tasks and serve those with a higher hierarchical rank than her. Indeed, Albanian society is structured around two main hierarchies: that of seniority and that of gender. The latter prevails over the former, meaning that a five-year-old boy enjoys a higher hierarchical status than his sixty-year-old grandmother. From an early age, an Albanian girl is conditioned to serve men and obey older women. In this way, when she eventually marries, she will not tarnish the reputation of the family that raised her. This ensures that the family, in turn, may one day fulfill its ultimate purpose: to secure wives for their sons from what Albanians call a good family. During adolescence, the social environment plays a major role in reinforcing this conditioning. Teenage girls frequently hear older women say: “You must help your mother now because she’s getting old.” The young girl indeed lightens her mother’s workload, but men are never explicitly identified as the beneficiaries of this help. Let’s return to this premature aging of the mother. This phenomenon becomes particularly pronounced when the eldest son reaches marriageable age. At that point, it is suggested that he find a wife who will help his mother, as she is getting old. The mothers who arrange marriages for their sons are generally between 40 and 50 years old. From then on, they mysteriously begin to lose their strength. Overnight, they relinquish certain tasks. Like prostitutes reaching retirement age — unsure of what to do with their future — these mothers decide to become madams in turn, managing and exploiting a horde of daughters-in-law, the full-time prostitutes of their sons. Consider these two excerpts from the Albanian customary law, the Kanun (5):

§22 Article 9. Rights of the mistress of the house: to command the women of the household, to send them to fetch water, collect firewood, bring food to the workers, irrigate, carry manure, harvest, dig, or thresh grain.

§23 Article 9. The mistress of the house does not cook, does not fetch water, does not gather firewood, does not irrigate, does not harvest, does not thresh, and does not bring food to the workers.

Descent

We previously saw that Albanian girls are conditioned to become devoted housewives. However, the essential quality of a woman lies in her ability to procreate. “A girl is a future wife, meaning a potential mother, yet destined to ensure the lineage of another, foreign family,” writes Albert Doja (6). In Albanian culture, marriage only becomes fully recognized when a woman gives birth to a male child; she ceases to be merely a wife and instead attains the status of a mother. Furthermore, infertile women are considered incomplete beings. In rare cases where a couple is unable to conceive, the husband may take a second or even a third wife — sometimes without releasing the previous ones — since no one would want a woman incapable of bearing children. The husband can never be held responsible for such a failing; even if a third marriage fails to produce a child, the issue is attributed to the will of God. To encourage the birth of a male child, various rituals and superstitions exist to summon all possible forces toward this achievement. For example, when the bride arrives at her husband’s home, a young boy is brought near her to increase her chances of giving birth to a son. The day before the wedding night, a young boy is rolled into the marital bed — once again, with the aim of ensuring the birth of a male heir (7). Newlyweds are wished u trashëgofshi! (May you have male heirs!). The birth of boys is particularly desired and celebrated, whereas the birth of a girl is announced almost casually in passing. If a boy is born, people wish him a long life, whereas if it is a girl, they reassure themselves by saying, “A girl is born to rock the boys.” (çika përkund djalin.) (8) Finally, people rejoice that the mother has survived childbirth, as if she had just given birth to Rosemary’s baby (9).

“Accepting a female child is, on the part of the father, an act of free generosity; a woman enters these societies only by a sort of grace that is granted to her, and not legitimately like the male.” (10)

The birth of a girl is sometimes even seen as a bad omen. In southern Albania, in Korçë, people believe that “the weather worsens, the fire in the hearth no longer lights, the roof tiles darken, and the house’s beams and rafters crack.” (11) Other Albanians believe they can predict a child’s sex: if the mother becomes more beautiful during pregnancy, they assume she will give birth to a boy, whereas if she suffers through the pregnancy with pigmentation spots on her face, it is taken as a sign that she will have a girl. Pregnant women themselves hope to bear a son, which sometimes has disastrous consequences. When a couple learns the sex of their child, they may resort to an illegal abortion. Albanian mothers often ignore the severe physical damage caused by such procedures, especially in the later stages of pregnancy. These women, subjected to immense social pressure, do not have control over their own bodies. This raises the question: do actual prostitutes even own their bodies? At least they sign contracts with men — whereas for Albanian women, their birth itself serves as a lifelong contract.

Today, Albanians who have two or three sons usually stop having children. However, if the firstborns are girls, the number of children in a family can grow significantly. In some cases, a family will consist of multiple daughters and a single son — the youngest, of course, since his birth makes the marriage officially “complete.” In such situations, the couple typically stops having more children. But in other cases, they may not settle for just one male heir; they aim for two. After all, an accident could befall the child, jeopardizing the continuity of the lineage. Consequently, brothers are often prevented from traveling together or taking common risks, for fear that one of them might perish. The case of an only son is particularly revealing. A boy with four sisters, for example, is considered an “only son” (djal për hasret). He is typically pampered and overprotected to an extreme degree. As the “golden child,” he alone embodies the continuity of the lineage, meaning that his four sisters and his mother must serve him with unwavering devotion. One advantage, at least, is that there are more people available to take turns rocking the only son — when they are not busy assisting their mother with household chores, of course. Even the names given to some Albanian girls reflect the deep-seated desire to conceive only male children. Names such as Shkurte (Shorten, Cut), Fikrije (Extinguish), and Nalije (Stop) exist because parents believed in the superstition that such names would prevent the future birth of more daughters.

The Milk Tree

Albanians distinguish between two hereditary lineages: the blood tree, representing the father’s lineage, and the milk tree, representing the mother’s lineage. The terms used for aunts and uncles differ depending on whether they belong to the blood tree or the milk tree (paternal aunt and uncle: hallë, axhë, or migj; maternal aunt and uncle: teze, dajë). Therefore, an Albanian mother is not considered a stranger in her father’s house. However, since she no longer lives there after her marriage, this often leads to serious conflicts between sisters-in-law within a family, as neither of them truly considers the household their own. As we have seen earlier, a woman often finds her salvation when the patriarch dies. Her husband then separates from his brothers, and once he owns his own house, he becomes the patriarch himself. The Kanun is also very precise about this distinction between the father’s and the mother’s family. For instance, if a woman is killed, it is not her son or her husband who must avenge her, but the family of her birth house. They are the ones who have the duty to restore their honor through vengeance. Thus, even in matters of violence and murder, the mother remains a stranger in her own home.

“§57 Article 28. The woman does not fall into blood feuds. The woman transmits blood to her parents.”

Regarding the murder of a woman, there was once an ancient custom that specifically tolerated such an act. While it is no longer practiced today, it applied in cases of marriage, where a girl refused to marry the man chosen for her by her father. The excerpt from the Kanun speaks for itself:

“§43 Article 17. The girl cannot reject the boy, even if she does not like him. If she refuses to go with the one who has taken her and if her parents support her, she cannot marry another as long as the first one is alive. […] If the girl does not want to go with the husband who has taken her, she will be handed over to him by force, along with a cartridge. If he sees the girl trying to escape and kills her with the cartridge given by her parents, her blood is not avenged, because he killed her with their cartridge.”

When the marriage is officiated, the father of the bride declares to the groom’s father: “Qika jem robi jotë” (My daughter, your slave). It is not merely a woman being transferred in a summer trade market, but a slave, a sex object, an inflatable doll, a prostitute destined for a life of servitude. The Albanian patriarch’s household could thus be considered a brothel training housewives and prostitutes alike. If she is not a prostitute, then what is the woman’s role in the house? The Kanun provides an answer to this as well:

“§44 Article 20. The Albanian woman receives no inheritance from her parents, neither in furniture nor in property. The Kanun considers the woman a supplement in the house.”

The woman is thus a supplement (tepricë). I wanted to check the definition of this word in the Larousse dictionary, and here is what I found: “Something added to something already considered complete.” Upon learning this, I advised my father — solely in the noble pursuit of keeping the flame alive with my mother, or rather, the raging fire, the volcanic eruption that justifies their mutual existence — to occasionally call her “my little supplement” or even “my little whipped cream.” I later reconsidered the latter suggestion, as it seemed more romantic, yet I did not wish to offend pastry chefs for whom whipped cream is an essential ingredient in their craft. What caught my attention was the tragicomic nature of the word supplement. However, you will also notice that the woman receives no inheritance. This seems only natural since she herself is part of the inheritance — she is property, transferred from one family to another. A property that is inherited, by definition, cannot inherit anything itself. A daughter is a burden; for a father, having a daughter is like betting on the wrong number at a casino — it is a guaranteed loss with no return on investment. The dowry he receives from the groom’s family serves as an exception, yet this price is more of a reward than true compensation. After all, no one raises a daughter for free. Thus, he is being thanked for successfully raising his daughter into a good housekeeper and a prostitute who will integrate seamlessly into the prostitution market that is Albanian society for women. And today, if parents push their daughters to pursue higher education, it is more to conform to a so-called modern and Western model than to encourage their daughters’ emancipation and financial independence. There is a paradox between what parents expect from their daughters as young girls and what they expect from them as future mothers.

Marriage

We have seen that marriage is an essential element in ensuring the continuity of the lineage. Here is what the Kanun says on the subject:

“§28 Article 11. To marry, according to the Kanun, means to establish a household or to add an additional member for the purpose of work and increasing the number of children.”

Marriage holds crucial importance among Albanians. Even today, it remains at the center of many family discussions, where various individuals feel burdened by the supreme duty of searching for the ideal wife from a good family. Women are scouted as if at fairs, in a marketplace where sisters and cousins act as the best scrutinizers and investigators, scouting the neighboring family brothels in search of a womb and a virgin. The Kanun is precise about marriage: it defines the rights and duties of spouses, regulates engagements, wedding preparations, and the organization of the bridal procession. Today, a convoy of cars is assembled to fetch the bride. Although the Kanun does not endorse bride kidnapping (13), the form of the procession — particularly the fact that the return route differs from the journey there — suggests that marriage could be a simulation of an abduction rooted in an ancient tradition. This theory is supported by Albanian historian and linguist Eqrem Çabej (14), novelist Ismail Kadare, and also by Simone de Beauvoir: “Primitive marriage is sometimes based on an abduction, whether real or symbolic: it is because violence against another is the most evident affirmation of their otherness.” (15) Young brides, once financially dependent on their fathers, are delivered in a polished and gilded package through the sacred institution of marriage to now live at the expense of their husbands. Moreover, the matchmaker (misiti) — the one who facilitated the agreement between the two families — receives a commission from the groom’s father if the marriage takes place (16). The financial transactions generated by marriages and their economic impact have likely resulted in a market far more lucrative than prostitution. One only needs to look at the amount Albanians invest in marrying off their sons — between €20,000 and €30,000. Likewise, in Kosovo, one can observe the countless massive, kitschy banquet halls built over the past decade, serving no other purpose than hosting marriage-related celebrations.

Albanian young men also face pressure from their families to get married. Fathers insist more than mothers that their sons find a wife: “When are you going to find a wife?” or “Find yourself a wife so she can take care of your aging parents!” There are various other formulations, but this last one seems the most interesting. Indeed, the Albanian father never had the freedom to choose his own wife, yet he retains the freedom to choose his son’s. Concealed behind the relationship of servitude that binds him to his daughter-in-law, he can indulge in the ostentatious pleasure of watching her move about before him, occasionally allowing himself a freeze-frame on her rear. Could this be seen as a form of vicarious sexual relationship through the son, with the father having a surrogate sexual connection with his daughter-in-law ?

Footnotes:

- Phonetically: kurv. This term, borrowed from the Slavic language, is used by Albanians in Kosovo. In Albania, the word lavire is more commonly used.

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, Volume I, Paris: Gallimard, Folio Essais, 1949, reissued in 1976, p. 17.

[Here is the full excerpt: “Man thinks of himself without woman. She does not think of herself without man. And she is nothing other than what man decides; thus, she is called ‘the sex,’ meaning that she appears essentially to the male as a sexual being: for him, she is sex, therefore she is so absolutely. She defines and differentiates herself in relation to man, not the other way around; she is the inessential in the face of the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute; she is the Other.”] - Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, Volume II, Paris: Gallimard, Folio Essais, 1949, reissued in 1976, p. 425.

- Albert Doja, Being Born and Growing Up Among Albanians: The Cultural Construction of the Person, Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000, p. 27.

- Author’s Note:

The Kanun is an Albanian customary code that has governed social rules in Albanian society. Although new laws are now in effect among Albanians, the Kanun remains deeply rooted in customs and often serves as a parallel legal system. The Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha had banned the application of the Kanun through a strict policy of repression. To redefine the family and the role of women, he modeled his policies on the Soviet system, which prided itself on claiming that there were no longer men or women, only workers. However, this model was not enough to eliminate gender inequalities. Indeed, over 40 years of communism in Albania failed to erase several millennia of male domination and eradicate patriarchy. This marks the main difference between Albania on the one hand and Kosovo and North Macedonia on the other. - Albert Doja, Being Born and Growing Up Among Albanians: The Cultural Construction of the Person, Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000, p. 34.

- ibid., p. 36.

- ibid., p. 35.

- Rosemary’s Baby — film by Roman Polanski — 1968.

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, Volume I, Paris: Gallimard, Folio Essais, 1949, reissued in 1976, p. 139.

- Albert Doja, Being Born and Growing Up Among Albanians: The Cultural Construction of the Person, Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000, p. 35.

- The word rob means “property” or “labor force” for Albanians; however, according to the Albanian Academy of Sciences, its proper definition is actually “slave.” (Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë: Instituti i Gjuhësisë dhe i Letërsisë, Fjalor i shqipes së sotme, Tiranë, Botimet Toena, 2002.)

- §29 Article 11 — The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini — Shtjefën Gjeçovi.

- Eqrem Çabej was an Albanian ethnologist and linguist (1908–1980).

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, Volume I, Paris: Gallimard, Folio Essais, 1949, reissued in 1976, p. 128.

- §38 Article 15 — The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini — Shtjefën Gjeçovi.